“We’re doing a series on the ologies,” the radio producer said, “and we’d like you to talk about oneirology, the scientific study of dreams.”

Ah, the ologies, I thought, looking back to my university student days, and the exciting ologies on offer back in the very early 1970s. I had been channelled along the serious science route through grammar school: chemistry and physics, since biology was considered more suitable for arts students. Thankfully I was required to study biology – my first ology – at university as it was a prerequisite for biochemistry, my chosen major. Genetics, neurobiology, and a very exciting new subject, ecology, won me over, and I switched to a zoology degree to keep my options open. I loved the texture and weight of the ecology textbook as much as I loved the field trips out into nature, and almost as much as I loved ethology, the scientific study of animal behaviour, a subject our head of department viewed with suspicion, believing, I think, that it was impossible to apply scientific principles to animal behaviour. I ended up studying developmental neurobiology with him, and I wonder what he would think of me today, working in and teaching the art and science of dream interpretation. (I sense his eyeroll, and his smile.)

The first serious scientific study of dreaming was published by Nathaniel Kleitman and Eugene Aserinsky in 1953, the year before I was born.

Aserinsky observed his son’s eyes fluttering during periods of heightened brain activity during sleep. He coined the term REM (Rapid Eye Movement). In 1957, Kleitman and William Dement woke people up during REM and discovered that 80% of them were dreaming at the time.

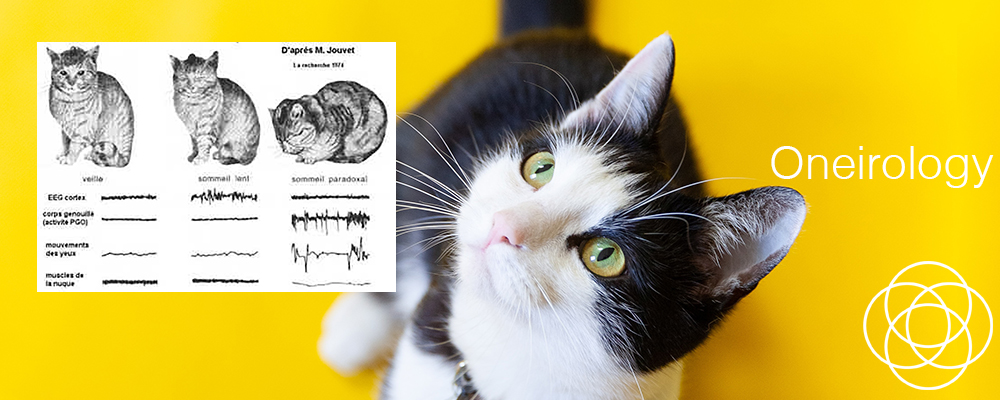

But it was Michel Jouvet’s 1958 work that got my attention during my university years. He discovered that when an area of a cat’s brain was severed, the cat would move about during REM sleep, prancing around as if wide awake. Jouvet deduced the cat was acting out its dreams because its motor muscles were no longer inhibited (by the neurotransmitters produced in that part of the brain) during sleep. He effectively showed that dreaming occurs during heightened brain activity: an active mind, a sleeping body. He named dreaming sleep ‘paradoxical sleep’.

In summary, these studies concluded that sleep, far from being a state of brain inactivity, is an active state where the brain processes information as intensely as it does during waking hours.

I began my dream research in the early 1990s, and although I didn’t seek publication in the scientific journals, I observed the relationship between people’s daytime experiences and their dreams in the following 1-2 days. I noted symbols, themes, issues, and emotions from waking life appearing in their dreams, either directly or in symbolic or allegorical form, and I noticed the ways their dreams worked at resolving conflicts, finding possible solutions, or overwriting past attitudes and patterns with new ones.

Although three of my books on dreams and dreaming were published during the 1990s (1994, 1995, 1998), and I discussed dreams and dreaming widely on various well-regarded radio stations, the worldview on dreams during that decade was very much ‘new age’. In more recent years, it has been such a pleasure to witness increasing understanding and acceptance of both the science and art of understanding the function of dreams and dreaming.

Here’s a fun one: in 2000, Robert Stickgold broke the lull in scientific publishing of dream research with his Tetris experiments. Essentially, he trained seventeen people to play Tetris, the computer game where you organise tumbling shapes into patterns. He woke them up during their hypnagogic sleep (that early period of sleep where you see dreamlike images) and found that sixty percent of the participants reported seeing Tetris images or other reverberations of their experiences. Some of the participants were amnesiacs, with no short-term memory, yet they too saw Tetris-like images during their hypnagogic dreams. Not only did his work confirm that dreams seem to process waking life experiences, but he also noted that the images were most often seen on the second night after the games, fitting with my (unpublished) observations that our dreams process our experiences of the previous 1-2 days. (Here’s an article about Stickgold’s Tetris experiments in Scientific American.)

Huge advances in the understanding of dreams and dreaming from a scientific – oneirological – point of view have been published since then, and it’s now widely accepted that while our NREM (Non-REM period) dreams help us to consolidate facts, our REM dreams process the more emotional aspects of our experiences, consolidate recent memories, and reinforce (or edit, or delete) older memories.

As a dream analyst, dream interpreter, dream therapist, and dream alchemist, my interest is exploring dreams to see how they handle the conflicts between our recent experiences and our older, more established ones: when do the older experiences prevail, when do newer ones overwrite older ones, how are new experiences interwoven with older experiences or memories, what remains conflicted, what is resolved within a single life-changing dream? What problems do we solve when we ‘sleep on it’? What wonderful synergies occur when the old and the new bubble together in one big melting pot and come up with something entirely new: a new perspective, a fresh insight? How can our dreams – explored and interpreted according to professional standards – help us to understand ourselves and our lives at such a deep level that we can step into a new day with new eyes, enriched, lightened, and enlightened?

You might also enjoy