What have Robert Louis Stevenson, Stephen King, and Stephanie Myer got in common? They’re world famous authors, they’ve written dark novels (horror or vampires), and they share similar names. But that’s not all. They’ve each based at least one of their books on a dream.

Stephanie Myer had written a chapter here and there over the years, but had never completed a book. Then one night she dreamed of an intense conversation between an “average girl” and a “fantastically beautiful, sparkly” guy who was also a vampire. They were falling in love yet the vampire, intoxicated by the scent of the girl’s blood, was having difficulty holding back from killing her. What should they do?

On waking, intoxicated by the scent of a compelling question and a good story and not wanting to lose the dream, Myer typed it out.

On waking, intoxicated by the scent of a compelling question and a good story and not wanting to lose the dream, Myer typed it out. From there she was hooked, writing every day. The book became Twilight, and the dream was embodied in Chapter 13. Within six months of the dream, the book was written and accepted for publication, then there was the movie, and to date 116 million copies of the Twilight saga have been sold worldwide. All inspired by a dream.

Stephen King is on record for rubbishing Myer’s writing ability, yet understands the dream thing, having used several of his own dreams for ideas for his novels. Misery, he told Stan Nicholls, began with a dream:

“I fell asleep on the plane,” he recalls, and dreamt about a woman who held a writer prisoner and killed him, skinned him, fed the remains to her pig and bound his novel in human skin. His skin, the writer’s skin. I said to myself, ‘I have to write this story.’ Of course, the plot changed quite a bit in the telling.”

When interviewed in 26 Writers Talk About Their Dreams and the Creative Process, by Naomi Epel, King said: “One of the things that I’ve been able to use dreams for in my stories is to show things in a symbolic way that I wouldn’t want to come right out and say directly. I’ve always used dreams the way you’d use mirrors to look at something you couldn’t see head-on—the way that you use a mirror to look at your hair in the back. To me that’s what dreams are supposed to do. I think that dreams are a way that people’s mind’s illustrate the nature of their problems. Or maybe even illustrate the answers to their problems in symbolic language.”

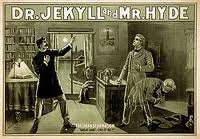

Robert Louis Stephenson had a problem, as he described in A Chapter on Dreams in Across the Plains (1892):

For two days I went about racking my brains for a plot of any sort; and on the second night I dreamed the scene at the window – Robert Louis Stevenson

He had been trying to find a story, “a body, a vehicle, for that strong sense of man’s double being which must at times come in upon and overwhelm the mind of every thinking creature.” His search intensified until, “For two days I went about racking my brains for a plot of any sort; and on the second night I dreamed the scene at the window, and a scene afterward split in two, in which Hyde, pursued for some crime, took the powder and underwent the change in the presence of his pursuers. All the rest was made awake, and consciously …”

It was 1866, and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was “conceived, written, re-written, re-re-written, and printed inside ten weeks.”

Dreams have inspired novels, art, music, and movies throughout time, sometimes arriving seemingly spontaneously (Paul McCartney awoke, in 1965, from a dream in which he heard a classical string ensemble playing a “lovely tune”, which he captured immediately on piano and named Yesterday) and sometimes arriving as solutions to artists’ block or petitioned prayers to the creative muse before sleep.

Albert Einstein traced the roots of his Theory of Relativity to a dream he had as a young boy. He dreamed he rode a sledge, faster and faster until he was travelling as fast as light.

Scientists have slept on unresolved problems and awoken with dream solutions such as molecular structures (Friedrich Kekule’s 19th century dream of a snake swallowing its tail led to his realisation that the molecular structure of benzene was a ring, not an open-ended chain), and key experiments (Otto Loewi dreamed a neurophysiology experimental method that led to his 1936 Nobel prize for his discovery of chemical neurotransmitters).

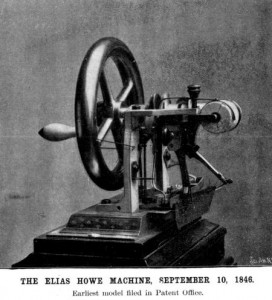

Many an inventor has taken a problem to bed and found the solution in a dream. How did a dream of cannibals lead to the invention of this sewing machine?

Many an inventor has taken a problem to bed and found the solution in a dream. In the 1840’s, Elias Howe was sweating on the problem of inventing a sewing machine that worked efficiently. He dreamed he was surrounded by cannibals who were about to eat him. Each cannibal thumped his spear on the ground, until, just before the critical moment, Elias noticed that just behind the tip of each spear was a hole. He woke up in the nick of time, and that’s where the hole in the sewing machine needle is to this day. Howe patented the lockstitch mechanism (where the needle takes the thread through the fabric and locks it with a second thread from a spool beneath the fabric) in 1846.

In each of these examples, the dreamer was satisfied with the idea or solution the dream presented, though closer examination of the dreams would have added personal insight. Just look at Howe’s theme about sweating on being eaten alive! The search for a solution to the sewing machine problem was potentially consuming him. And King’s dream theme explores unconsciously feeling ransomed and restricted by fear of vulnerability.

Dreams are the result of your dreaming mind and brain processing your conscious and unconscious experiences of the last 24-48 hours. These experiences include emotions, feelings, issues, challenges, unresolved problems, new learning, new or shifted perspectives, ideas, and insights. These recent experiences are compared to similar past experiences (which is why you often see symbols from your past in your dreams) and your dreaming mind then either consolidates your long held beliefs about life or creates new ones. In this way, interpreting a dream enables you to understand your mindset, the old beliefs that work well for you, the old beliefs that keep you stuck or work against more beneficial outcomes, and the new beliefs and fresh perspectives that will influence you into your future.

Recurring, unresolved dreams usually reflect recurring, unresolved issues or ways of seeing the world or seeing a problem. On those magical nights when your dreaming brain gets past old stuck beliefs and ways of seeing the world, you may wake up with a brilliant idea, whether that is an insight into a relationship issue, a new way of doing business, a solution to writers’ block, or a long sought plot for a novel.

You can precipitate this by contemplating the precise problem you want to solve as you fall asleep. Clearly Robert Louis Stevenson and Elias Howe did this. These days we call it dream incubation.

What you discover about yourself – and your unconscious mind – may make the difference between succeeding and failing with your idea.

If you awake from a dream with a eureka moment, or if you’re directly inspired by the storyline or dream metaphor to create a product, service, business, or work of art, go ahead! If you’d like to discover additional personal insight, set aside some time to explore and interpret your dream. What you discover about yourself – and your unconscious mind – may make the difference between succeeding and failing with your idea.